It’s Election Day in Arizona and elderly voters in Maricopa County are told by phone that local polling places are closed due to threats from militia groups.

Meanwhile, in Miami, a flurry of photos and videos on social media show poll workers dumping ballots.

The phone calls in Arizona and the videos in Florida turn out to be “deepfakes” created with artificial intelligence tools. But by the time local and federal authorities figure out what they are dealing with, the false information has gone viral across the country.

This simulated scenario was part of a recent exercise in New York that gathered dozens of former senior U.S. and state officials, civil society leaders and executives from technology companies to rehearse for the 2024 election.

The results were sobering.

“It was jarring for folks in the room to see how quickly just a handful of these types of threats could spiral out of control and really dominate the election cycle,” said Miles Taylor, a former senior Department of Homeland Security official who helped organize the exercise for the Washington-based nonprofit The Future US.

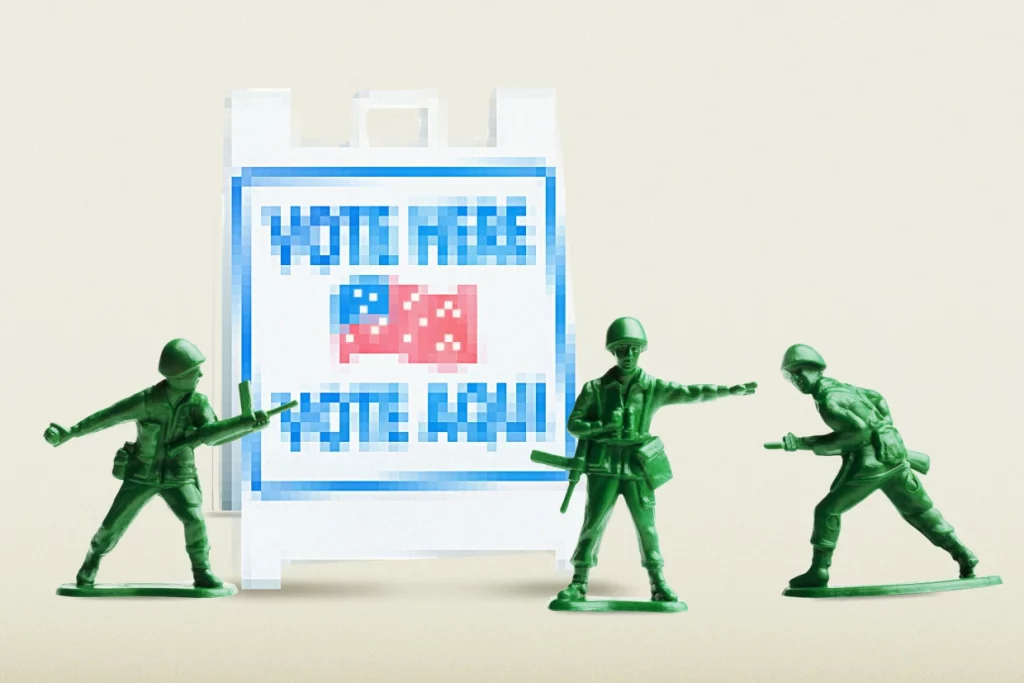

Dubbed “The Deepfake Dilemma,” the exercise illustrated how AI-enabled tools threaten to turbocharge the spread of false information in an already polarized society and could sow chaos in the 2024 election, multiple participants told NBC News. Rather than examining a singular attack by a group or hostile regime, the exercise explored a scenario with an array of both domestic and foreign actors launching disinformation, exploiting rumors and seizing on political divisions.

The organizers and participants in the war game spoke exclusively to NBC News about how it played out.

They said it raised worrisome questions about whether federal and local officials — and the tech industry — are prepared to counter both foreign and domestic disinformation designed to undermine public confidence in the election results.

Current U.S. officials say privately they share those concerns and that some state and local election agencies will be hard-pressed to keep the election process on track.

The exercise illustrated the uncertainty surrounding the roles of federal and state agencies and tech firms seven months before what is expected to be one of the most divisive elections in U.S. history. Does the federal government have the ability to detect an AI deepfake? Should the White House or a state election office publicly declare that a particular report is false?

Unlike a natural disaster, in which government agencies work through a central command, America’s decentralized electoral system is entering uncharted territory without a clear sense of who’s in charge, said Nick Penniman, CEO of Issue One, a bipartisan organization promoting political reform and election integrity.

“Now, in the last few years, we in America are having to defend assaults on our elections from both domestic and foreign forces. We just don’t have the infrastructure or the history to do it at scale because we’ve never had to face threats this severe in the past,” said Penniman, who took part in the exercise.

“We know a hurricane is eventually going to hit our elections,” said Penniman. But in the exercise, “because patterns of working together haven’t formed, few people understood exactly how they should be coordinating with others or not.”

In a mock “White House Situation Room” around a long table, participants played assigned roles — including as directors of the FBI, CIA and the Department of Homeland Security — and sifted through the alarming reports from Arizona and Florida and numerous other unconfirmed threats, including a break-in at a postal processing center for mail-in ballots.

Conferring with the tech companies, players who were “government officials” struggled to determine the facts, who was spreading “deepfakes” and how government agencies should respond. (MSNBC anchor Alex Witt also took part in the exercise, playing the role of president of the National Association of Broadcasters.)

In the exercise, it was unclear initially that photos and video of poll workers tossing out ballots in Miami were fake. The images had gone viral, partly because of a bot-texting campaign by Russia.

Eventually, officials were able to establish that the whole episode was staged and then enhanced by artificial intelligence to make it look more convincing.

In this and other cases, including the fake calls to Arizona voters, the players hesitated over who should make a public announcement telling voters their polling places were safe and their ballots secure. Federal officials worried that any public statement would be seen as an attempt to boost the chances of President Joe Biden’s re-election.

“There was also a lot of debate and uncertainty about whether the White House and the president should engage,” Taylor said.

“One of the big debates in the room was whose job is it to say if something’s real or fake,” he said. “Is it the state-level election officials who say we’ve determined that there’s a fake? Is it private companies? Is it the White House?”

Said Taylor, “That’s something that we think we’re also going to see in this election cycle.”

And although the war game imagined tech executives in the room with federal officials, in reality, communication between the federal government and private firms on how to counter foreign propaganda and disinformation has sharply diminished in recent years.

The once close cooperation among federal officials, tech companies and researchers that developed after the 2016 election has unraveled due to sustained Republican attacks in Congress and court rulings discouraging federal agencies from consulting with companies about moderating online content.

The result is a potentially risky gap in safeguarding the 2024 election.

State governments lack the resources to detect an AI deepfake or to counter it quickly with accurate information, and now technology companies and some federal agencies are wary of taking a leading role, former officials and experts said.

“Everybody’s terrified of the lawsuits and … accusations of free speech suppression,” said Kathy Boockvar, former Pennsylvania secretary of state, who took part in the exercise.

The New York war game, plus similar sessions being carried out in other states, is part of a wider effort to try to encourage more communication between tech executives and government officials, said Taylor.

But in the world outside the war game, social media platforms have cut back teams that moderate false election content, and there’s no sign those companies are ready to pursue close cooperation with government.

State and local election offices, meanwhile, face a significant shortage of experienced staff. A wave of physical and cyber threats has triggered a record exodus of election workers, leaving election agencies ill-prepared for November.

Concerned about understaffed and inexperienced state election agencies, a coalition of nonprofits and good-government groups are planning to organize a bipartisan, countrywide network of former officials, technology specialists and others to help local authorities detect deepfakes in real time and respond with accurate information.

“We’re going to have to do the best we can — independent of the federal government and the social media platforms — to try to fill the gap,” said Penniman, whose organization is involved in the election security effort.

Boockvar, the former secretary of state, said she hopes nonprofits can act as a bridge between the tech companies and the federal government, helping to maintain communication channels.

Some of the largest AI tech firms say they are introducing safeguards to their products and communicating with government officials to help bolster election security before the November vote.

“Ahead of the upcoming elections, OpenAI has put in place policies to prevent abuse, launched new features to increase transparency around AI-generated content, and developed partnerships to connect people to authoritative sources of voting information,” said a spokesperson. “We continue to work alongside governments, industry partners, and civil society toward our shared goal of protecting the integrity of elections around the world.”

The internet, however, is filled with smaller generative-AI companies that may not abide by those same rules, as well as open-source tools that allow people to build their own generative-AI programs.

An FBI spokesperson declined to comment on a hypothetical situation, but said the bureau’s Foreign Influence Task Force remains the federal lead “for identifying, investigating, and disrupting foreign malign influence operations targeting our democratic institutions and values inside the United States.”

The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency said it’s working closely with state and local agencies to protect the country’s elections.

“CISA is proud to continue to stand shoulder to shoulder with state and local election officials as they defend our elections process against the range of cyber, physical, and operational security risks, to include the risk of foreign influence operations,” said senior adviser Cait Conley.

For many of those in the room for the exercise, the scenarios drove home the need to develop an ambitious public education campaign to help voters recognize deepfakes and to inoculate Americans from the coming onslaught of foreign and domestic disinformation.

The Future US and other groups are now holding talks with Hollywood writers and producers to develop a series of public service videos to help raise awareness about phony video and audio clips during the election campaign, according to Evan Burfield, chief strategy officer for The Future US.

But if public education campaigns and other efforts fail to contain the contagion of disinformation and potential violence, the country could face an unprecedented deadlock over who won the election.

If enough doubts are raised about what has transpired during the election, there’s a danger that the outcome of the vote becomes a “stalemate” with no clear winner, said Danny Crichton of Lux Capital, a venture capital firm focused on emerging technologies, which co-hosted the exercise.

If enough things “go wrong or people are stuck at the polls, then you just get to a draw,” Crichton said. “And to me that is the worst-case scenario. … I don’t think our system is robust enough to handle that.”