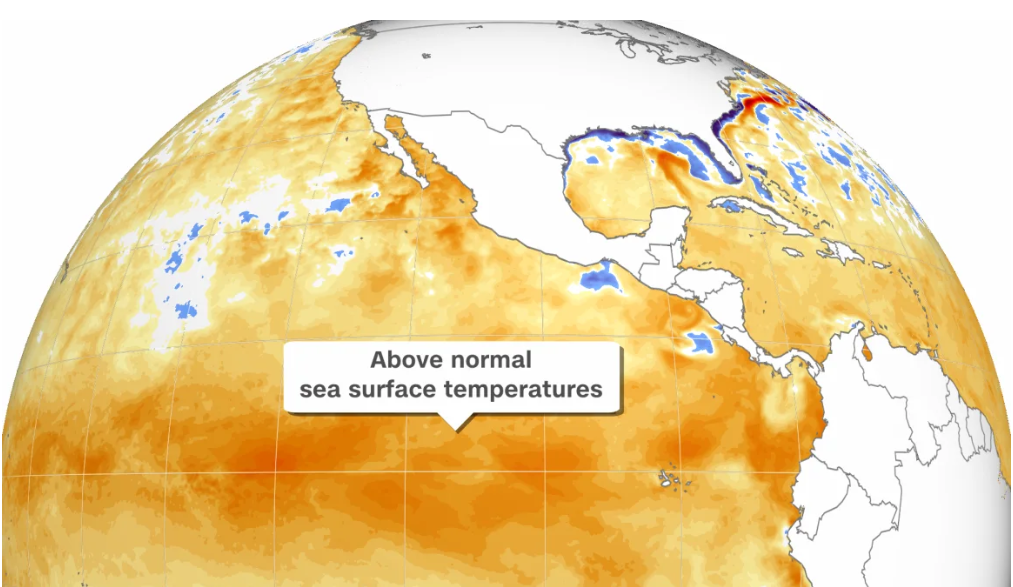

(Sea-surface temperature anomalies are shown in the area of the eastern Pacific Ocean where a very strong El Niño is present on Wednesday, February 7, 2024. Darker oranges represent warmer than normal conditions while blues represent cooler than normal conditions. These ocean temperatures help determine the strength of El Niño. )

The current El Niño is now one of the strongest on record, new data shows, catapulting it into rare “super El Niño” territory, but forecasters believe that La Niña is likely to develop in the coming months.

One of the main ways scientists determine whether El Niño is present, and a key indicator of its strength, is through ocean surface temperatures. And from November to January, the temperature of the tropical Pacific Ocean where El Niño originates was 2 degrees Celsius warmer than normal, according to NOAA’s Climate Prediction center – a threshold that has only been breached six times on record. It means a very strong El Niño is ongoing.

But this so-called super El Niño’s strength won’t last long – it has reached its peak strength and is headed on a downward trend, said Michelle L’Heureux, a climate scientist with the Climate Prediction Center.

“We’re slightly past peak [strength] at this point,” L’Heureux told CNN.

Forecasters believe the switch could get totally flipped to La Niña – cooler than average conditions in the eastern tropical Pacific – as soon as summer, but more likely by fall, and issued a La Niña watch on Thursday.

El Niño influences weather around the globe, so its strength and demise will continue to have an impact on the weather we experience in the coming months.

The stronger an El Niño gets, the more likely it is to influence the global weather over time. But its impact is measured on a seasonal timescale, and not in terms of individual weather events, L’Heureux explained.

El Niños have hallmark seasonal signs, particularly on winter in the US.

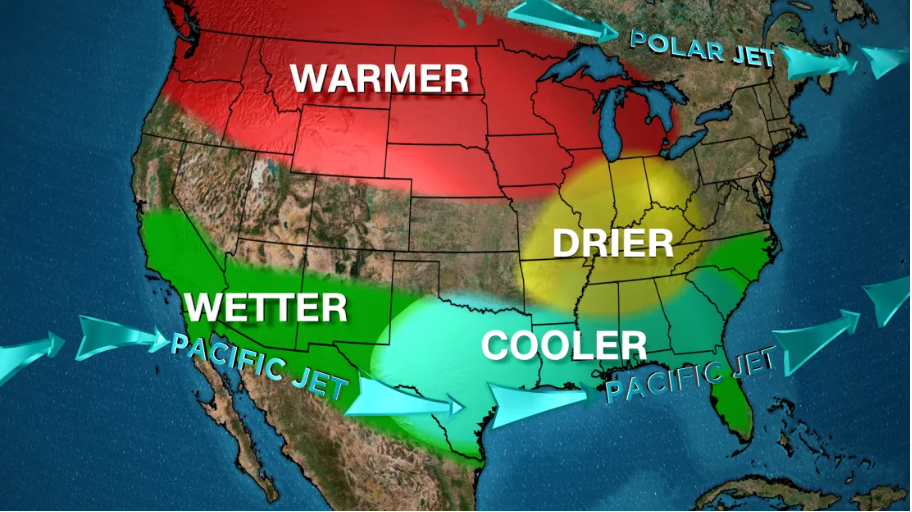

(Average conditions during an El Niño winter across the continental US)

A warmer-than-average winter with less snow across the northern tier of the US is one of these signs. This exact scenario is unfolding this winter. Multiple states in the region experienced the warmest-ever December and an overall toasty January with paltry amounts of snow – a trend that’s continuing into February.

El Niño also manifests as a wetter-than-average winter for the southern tier of the US as it often points the storm-steering jet stream south.

A serious drought in parts of the South has largely been wiped out this winter by repeated bouts of rain from storm systems. And California was just deluged by back-to-back potent atmospheric river-fueled storms that unloaded record rainfall and hundreds of mudslides.

El Niño has been known to enhance atmospheric river events on the West Coast.

“It’s difficult to attribute any single weather system or series of them to El Niño. With that said, it seems probable that there were some links to El Niño [with California’s storms],” L’Heureux noted.

The additional source of heat from warmer water in the eastern Pacific Ocean can be especially impactful to weather patterns in the western portions of both Americas that border the Pacific.

The recent disastrous, deadly fires in Chile reflect the El Niño connection. The pattern is linked to decreased precipitation in the northern part of the country which contributed to extensive drought that left areas tinder-dry.

(Aerial view of the destruction wrought by forest fires in the Valparaiso region of Chile on February 6, 2024.)

El Niño has also left its fingerprints on temperature and precipitation patterns in several other continents, including South America, Africa, Australia and parts of Asia, according to L’Heureux.

But L’Heureux is careful to caution that not every extreme weather event can be attributed directly to El Niño in a warming world.

“El Niño impacts don’t occur in isolation anymore. There’s certainly a climate change component,” L’Heureux said.

Human-caused climate change is driving up global temperatures, leading to more frequent and intense extreme weather events.

La Niña watch issued

A La Niña watch is now in effect, meaning conditions are favorable for a La Niña to form within the next six months, according to a forecast released by the CPC Thursday.

The center is eyeing this transition to unfold during the summer months, with La Niña conditions increasingly likely to be in effect through the fall.

There is a 55% chance of La Niña to develop from June to August and a 77% chance from September to November, according to L’Heureux and the forecast.

This abrupt pattern flip is not unprecedented. Historically, strong El Niños are followed by La Niña conditions about 60% of the time, L’Heureux said.

Depending on when – or even if – La Niña materializes, this large-scale pattern flip could have significant implications for how the rest of the year’s weather plays out.

La Niñas often produce the opposite weather patterns as El Niño, including a more active Atlantic hurricane season. La Niña conditions were in place for a portion of the most active Atlantic hurricane season on record: 2020.

A quicker switch to La Niña could mean more of an impact on the upcoming hurricane season, which begins in June and typically peaks in September – particularly if oceans stay exceptionally warm.

Last year’s Atlantic hurricane season was unusually active amid record warm oceans, despite attempts by El Niño to tamp down activity.